In 2024, the UK recorded over 9.5 million criminal incidents, a 12% increase on the previous year. Many communities continue to face difficult social conditions and the evidence increasingly shows that enforcement alone is not enough. To prevent crime before it starts, we need to address its root causes. Football, the most popular sport in England, already plays an unrecognised role in doing just that.

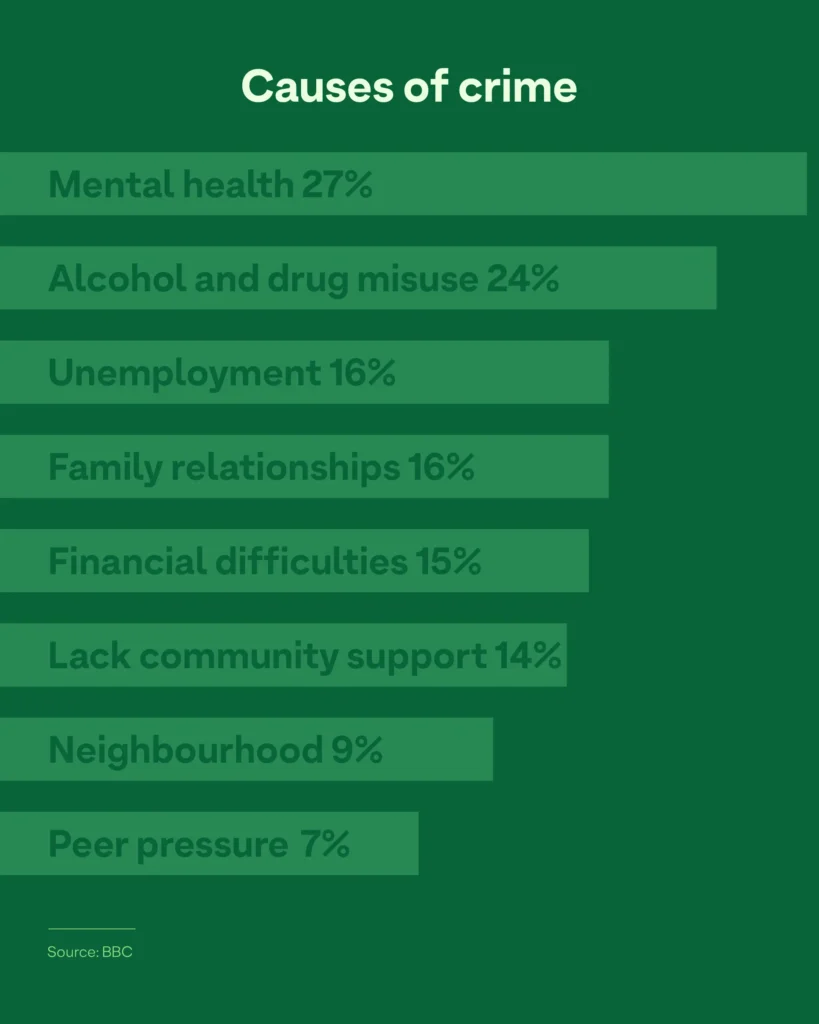

What the numbers say about why crime happens

According to BBC research and ONS data, the most common underlying factors linked to crime include mental health (27%), alcohol and drug misuse (24%), unemployment (16%), family breakdown (16%), financial stress (15%), and a lack of community support (14%). These issues are complex but they are not fixed by surveillance or punishment alone. What helps is meaningful engagement, social connection and regular, positive routines. Football can reduce crime effectively and offers all three.

Football’s scale and appeal

The FA reports that 5.1 million children and 10.6 million adults in England currently play football. That is 15.7 million people or almost one in four of the population. No other team sport comes close. Sport England’s Active Lives data confirms that football is the top sport for participation across all demographics. Roughly 40% of all people who play team sports choose football.

This matters because football reaches the people most likely to be affected by crime or social disconnection. It appeals across gender, class and age. It requires minimal equipment. It can be played in nearly any space. It feels familiar and welcoming to many who would not attend a formal programme or traditional club.

Football as prevention, not reaction

The Premier League Kicks programme has shown how football can reduce crime directly. In North London, a project with Arsenal FC helped reduce youth crime by 66% within one mile of the site. In Sussex, police saw a 65% drop in crime linked to teenagers who took part in weekly sessions. In Manchester, anti-social behaviour dropped by 28.4% during session times.

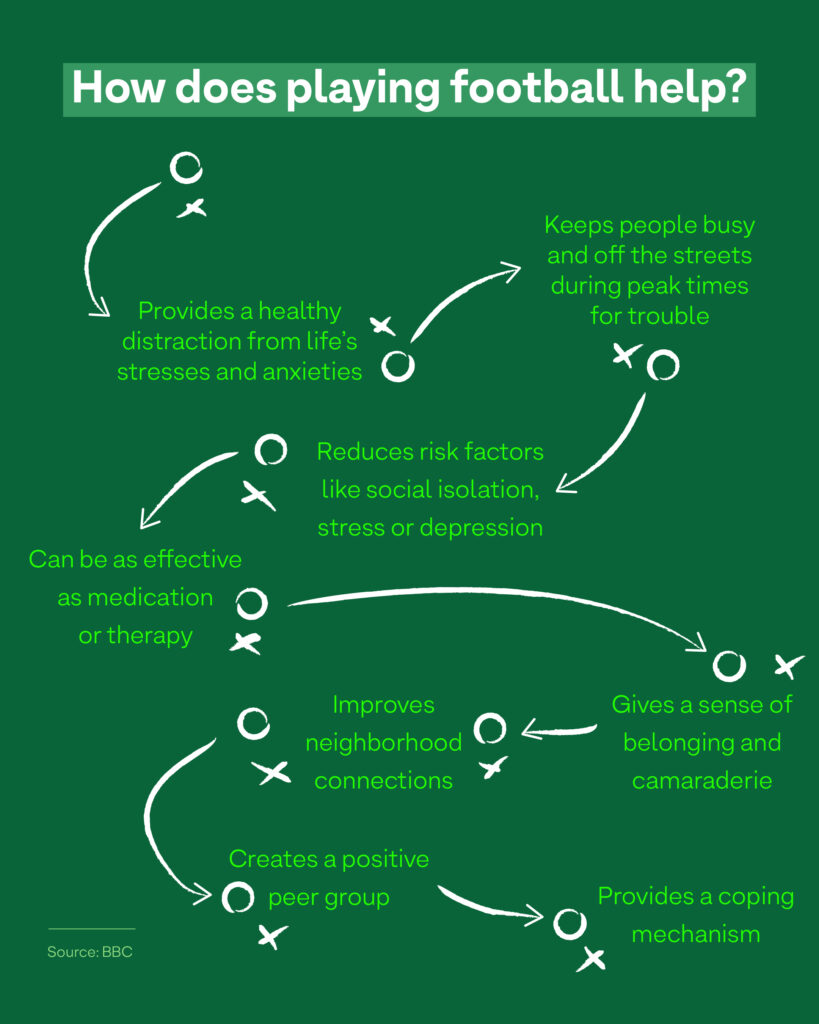

These are not small effects. They demonstrate that when people have regular football sessions, they are far less likely to offend. The reasons are clear. Football offers structure, prosocial environment, stress relief and purpose. Many participants report that football gives them something to look forward to and a reason to avoid trouble.

The impact on mental health and community

Poor mental health is a major risk factor for crime. Football helps reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, often matching the effectiveness of medication or therapy. It keeps people active. It provides a sense of belonging. In many communities, a weekly football game is a lifeline for those who feel isolated or excluded.

Football also creates social bonds. Sport England research shows that football generates 1.77 billion hours of social interaction each year in England. Participants tend to report higher levels of trust and social cohesion. This is particularly strong among lower-income groups. The sense of shared identity that comes with football helps create stronger, more resilient neighbourhoods.

A proven football model without recognition

Since 2014, Football for All has been quietly building one of the largest community football programmes in the country. Now delivering over 2,500 games each month in 51 local authorities. 61% of the games take place in areas classed as deprived or in need of support where football can reduce crime the most.

The model is simple. 1-hour, small-sided games for adults. No club commitment. No trials. Just turn up and play. Sessions are open to all abilities, with both co-ed and women-only options. Every pound paid goes back into expanding local access. The volunteers, known as Game Hosts, receive guidance to welcome newcomers, split teams and keep a safe, friendly atmosphere.

Many participants are not part of other sports clubs. Some have been inactive for years. Others had negative experiences with school sports or competitive environments. Football for All gives them a space to reconnect with the game, improve their health and meet people.

A cost-effective way that football can reduce crime

Crime is expensive. Youth crime alone costs the public roughly £1.5 billion per year. Keeping one person in a Young Offender Institution costs nearly £100,000 annually. By contrast, supporting a weekly football session costs a fraction of that. It also builds skills, confidence and relationships that benefit people for life.

Local authorities often invest in multi-sport courts, but these frequently go underused. Sport England estimates that 96% of councils do not have enough 3G or 4G football pitches. The Football Foundation says England needs at least 2,000 more astro pitches to meet grassroots demand.

If more councils supported Football for All or similar programmes, the benefits would multiply. Every new participant is another reason to justify funding for better pitches. Every game reduces isolation and offers a positive alternative to crime.

Too many local plans still treat football as an afterthought. Funding is often spread thin across sports with far smaller followings. A fairer model would invest 60 to 70% in football, with remaining funds supporting additional activities. Where developers offer sport facilities, councils should ask for proper artificial turf pitches, not generic concrete courts.

Partnerships between local authorities, schools, police and football groups already work. But they need consistent support. Football for All operates on limited resources yet delivers outcomes in mental health, social connection and crime prevention. Backing should not be an optional extra. It should be central to every strategy aimed at safer communities.

Football will not fix every problem in society. But it is a proven, popular and cost-effective way to improve mental health and connect people. In 2025, with crime rising and budgets stretched, we cannot afford to overlook practical answers hiding in plain sight. Football is one of them. It is time we started treating it as such.

Sources: Official data from Sport England, The FA, and the Football Foundation on participation rates and social impacts of football. Home Office and ONS statistics on crime. Case studies from the Premier League Kicks programme and various sports-crime reduction pilots and reports by the Youth Endowment Fund and academic institutions on sports as a tool for violence prevention have all been drawn on to underpin the facts and figures above.